How Do You Spell That Again?

There are no fewer than nineteen (and counting) modern variants in the spelling of the Saydjari family name:

- Alsayjare

- Alsijary

- Saijari

- Saijary

- Saydari

- Saĝar

- Sayjari

- Segari

- Seijari

- Seijary

- Sejari

- Sejary

- Seyceri

- Sijare

- Sijarey

- Sijari

- Sijarrey

- Sijary

- Syjari

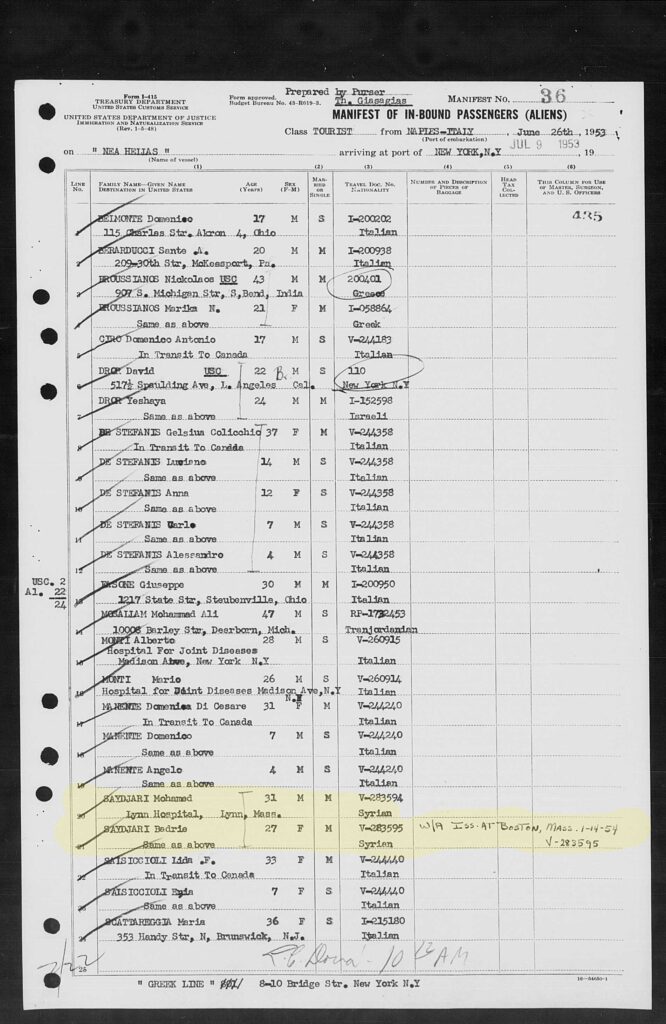

Ellis Island Awaits

What’s In a Name?

“A Rose By Any Other Name…”

Why are there so many variants of the family name? In short, there are both cultural and language differences at play here.

T.E. Lawrence (yes, the Lawrence of Arabia), who lived among the Arabs for several years before and during World War I and who spoke not only standard Arabic but several local dialects, probably summed it up more concisely than anyone else in answer to exasperated queries from his publisher about inconsistent spellings of Arabic names in his manuscript Revolt in the Desert:

“Arabic names won’t go into English, exactly, for their consonants are not the same as ours, and their words, like ours, vary from district to district. There are some `scientific systems’ of transliteration, helpful to people who know enough Arabic not to need helping, but a wash-out for the world. I spell my names anyhow, to show what rot the systems are.”

Arabic Language Origins

Here then, is the extended explanation. The two languages come from entirely different language families: apples and oranges, really. English comes from the large and newer Indo-European language family. Arabic comes from the ancient Semitic language group. Among the Semitic languages, the most spoken are Arabic, Hebrew, Tigre, and Aramaic.

Transliteration

Before we get any further into this, remember that there is still no agreed-on way of transliterating Arabic into English. This is why we had the former leader of Libya, written as Gaddafi, Qaddafi, Al Qathafi, Qadhafi, and El Ghadafi. First, only eight Arabic consonants – B, F, K, L, M, N, R, and Z – have an indisputably equivalent letter in the Roman (English) alphabet. Moreover Arabic also has two distinct consonants that sound like S, and the same applies to D, H, and T. Arabic has eight vowels/diphthongs and 28 consonants. English only has five vowels (or six, if you include the letter y). This has led to various English spellings of Arabic words.

And so, it is little wonder that translating names from one language to another was variable at best. Add to this the fact that the ship’s purser was responsible for creating the passenger manifests used to assign the official names at ports of entry, and you have a recipe for the many name variant phenomenon. The ship’s purser often did not speak the passenger’s native tongue, adding to the confusion. In fact, whatever was written on the manifest by the purser was recorded by the immigration official.

Arab Name Construction Elements

In addition to issues with transliteration, the construction of Arab names is significantly different. Conventionally Arab names can have, but don’t have to have, five parts, although it’s highly unusual that a single name would have all five components. The five are ism, kunya, laqab, nasab, and nisba.

First of all, Arabic names are patrilineal. This means you use your given name, followed by your father’s name, followed by your grandfather’s name…etc. The ism is simply a first name, such as Muhammad, Fatimah, Sultan, Maha, Rami, Omar, etc. And so, the ism can consist of what in English looks like two or three words (e.g., Abdal Rahman). Thus my patrilineal name in the past would have been Rami bin Mohamed bin Rahman; Mohamed was my father, and Rahman was his father.

The next parts of the name are the laqab and the nisba which sort of serve the same purpose, which is to indicate a characteristic of the person named. They are usually added to the person’s name during their lifetime rather than being something they were born with.

The laqab is more of a nickname or a title. It’s not an official or social title; it’s a personal title similar to some European kings having names such as “Richard the Lionheart” or “Catherine the Great,” except in Arab culture, it is not limited to royalty or nobility.

Such nicknames follow the given or first name and usually relate to religion, nature, a descriptive, or of some admirable quality the person had (or would like to have); e.g., al-Rashid [the Rightly-guided], al-Fadl [the Prominent]. Other examples of a laqab include al-‘Abbas [the frowner], al-‘Ala’ [the exalted], al-A’rabi [the Arab], al-Haddad [the blacksmith], al-Hasan [the handsome], and al-Najjar+ [the carpenter].

The nisba ends with a “y” (or “I” depending on how you transliterate it. In my case, Saydjari indicates that my family is from the citadel of Shayzar. Shayzar was transliterated along the immigration path to Saydjari. Maybe that’s what you get when you travel to the United States on a Greek passenger ship. Saddam Hussein’s nisba was al-Tikriti, indicating his origins in the town of Tikrit. Gaddafi (al-Qadhafi) indicates Muammar’s membership of the Qadhadhfa tribe.

The nasab and the kunya denote parentage: the nasab indicates the parents; the kunya, children. The nasab is preceded by the word ibn or bin (son) or bint (daughter). Classically the nasab is more formal than a kunya.

In the modern world, the most prominent examples of the extended nasab are to be found among the remaining monarchies of the Gulf: the former King of Saudi Arabia may be correctly referred to as “Abdullah ibn Abdulaziz ibn Abdulrahman ibn Faisal ibn Turki ibn Abdullah ibn Muhammad ibn Saud ibn Muhammad ibn Muqrin Al Saud,” all the way back to his great (x7) grandfather. This is important for the Al Saud family because it shows that they are descendants of the man who founded the precursor to the modern Saudi State.

The kunya, which is preceded by abu (father) or umm (mother), is often used as a more familiar form of address. A kunya is normally given in honor of children (Abu Fatimah, Umm Muhammad). Some modern examples, such as the one given to Yasser Arafat, Abu Ammar, are chosen for close friends.

The current Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas is known as Abu Mazen, after his son. In Syria, Hafez al-Asad was sometimes referred to as Abu Basil after his son died in a car accident in 1994. Thus Bashar is occasionally called Abu Hafez after his son, who has his grandfather’s name. However, you can also use arbitrary names if you don’t have any children, and you wanted one, or something might stick to you unintentionally.

Abu Huraira was a close companion of the prophet Mohammed and a prominent Islamic figure. He did not have a daughter called Huraira; the name literally means “father of the kitten” it stuck to him because, as the story goes, he actually had a kitten that he loved and took with him wherever he went. The name remained even after the kitten became a cat and then eventually died of old age.

Colonial Influence

So classically, this complex system is how Arabic names were constructed. In the modern Middle East, primarily due to colonialism, people generally have adapted and taken a first and a last name. However, these elements may be derived from the classical forms listed above.

The classical forms were in more common use during my parents’ lifetimes from the 1920s through their immigration in the 1950s, especially in smaller, more remote villages. The kunya practice continues, the laqab is more or less extinct, and the nisba tends to be ignored except in reporting full names. The nasab, as discussed above, thrives in the Gulf and is more or less irrelevant everywhere else.

As an aside of historical interest, Arabic names have often become corrupted when used by Europeans. Examples, many from the medieval period, include Averroes, from ibn Rushd; Avicenna from ibn Sina; Achmed from Ahmad; Amurath from al-Murad; Saladin from Salah al-Din; Nureddin from Nur al-Din; Almanzor from al-Mansur; Rhases from Razi; and Avenzoar from ibn Zuhr.

OK, now let’s put it all together. Traditionally an Arab name is constructed as follows:

The kunya (if any), followed by personal name, followed by laqab (if any), followed by patrilineal sequence (as long as needed, with their own laqabs if any), followed by clan-based nisba (in the proper sequence of clans and sub-clans), followed by any other nisba he may have (if any) in no particular order.

Example

Here is a real-life example of a classic Arab name: Abu Ja’far Haruun Al Rasheed bin Muhammed Al Mahdi bin Abdullah Al Mansur bin Ali bin Abdullah ibn Al Abbas ibn Abdul Mutallib ibn Hashim Al Abbasi Al Hashimi Al Qurashi.

This translates to Father of Ja’far, Harun, the Wise son of Muhammed, the Guided son of Abdullah, the Victorious son of Ali, son of Abdullah, son of Al-Abbas, son of Abdul Muttalib son of Hashim the Abbasid the Hashimid the Qurashid. He has three nisbas; the first is the Abbasid clan (which gave its name to the dynasty) after his great great great grandfather Al Abbas ibn Abdul Mutallib, which is a sub-clan of the second, the Hashimid clan after his great great great great great grandfather.

The Hashimid clan is, in turn, a sub-clan of the Quraish tribe of Makka, his third nisba. At the beginning of his name, the kunya does not refer to a son he has; it was a Kunya he chose before he even got married – he never had a son called Ja’far. His Laqab Al Rasheed is often translated as “the wise,” it actually means more than just wise. Most English books on him translate it as “The Just.”

Based on modern conventions, the bin would be dropped; the kunya would be used socially only and not added formally to his name. The laqab would be treated like a nisba and added at the end together with his father and grandfather’s laqab, which would be appended to his name. So he would be called: Harun Muhammed Abdullah Ali Abdullah Al-Abbas Abdul Mutalib Hashim Al Abbasi Al Hashimi Al Qurashi Al Mansour Al Mahdi Al Rasheed. However, legally, only clan-based names remain, so the last three would be omitted.

Moreover, this long version is usually only used in official documentation such as birth certificates or naturalization papers and court proceedings such as trials. In everyday use, only three names are used and one family name, so he would most probably be: Harun Muhammed Abdullah Al-Abbasi – this is how it would be written in his ID card, passport, degree certificates, and employment records. His business card and how he presents himself to people would be Harun Al Abbasi – which pretty much looks a lot like “John Smith” to most Arabs.

So I guess that would make me: Abu Alexander (or Abu Allia), Rami Al Jirah bin of Mohamed Al Hasan Jirah bin Abdul Rahman Al Taajir ibn Al Shayzari. This translates roughly to Father of Alexander (Father of Allia) Rami, the surgeon son of Mohamed the Handsome Surgeon son the Abdul Rahman, the Merchant of the Shayzar clan.

Ottoman Influence

Oh, and let’s not forget that surnames were not even required or commonly used in the Ottoman Empire and other parts of the Middle East until around 1934 when a law was passed. Before then, people used their patrilineal names as noted above, and tacked on the name of the village in which they were born, e.g., al-Shayzari or their profession.

Clear? Good. Then perhaps you could explain it to me someday.